We Adopted Basketball

There is a community recreation center four blocks from where I live. It’s nestled into a residential block of the Richmond neighborhood in San Francisco, the entrance shaded by rows of multi-story flats on either side, with a gaggle of bushes that block the signage unless standing at an exact angle facing the building. Walking by it a few times every week, it is unassuming, mellow, tucked into the background — not too different from the rest of the neighborhood it serves.

The Richmond Rec is also free. It sports a small weight room, two treadmills, a dozen ping pong tables, a small half size pool, and a full length basketball court supporting 6 hoops. On Sunday mornings, after grabbing a pineapple bun from a bakery down the street, I’ll make my way over to get a few shots in and work up a sweat. If I get there around 9:30am, then I know I have just barely 30 minutes of time alone on the court, before I start to see a trickle of neighborhood kids looking for pickup games. By 10:30am, they’ve started two separate 5 on 5’s, with another dozen milling around the sidelines practicing crossovers or jumpshots. They are high school age at the latest, mostly boys, and without compromise, they are almost all Asian.

I was born in Texas, in a small suburb of Dallas called Grand Prairie. Growing up, I was frequently the only Asian kid in my class, so as an attempt to keep me connected with my native culture, my parents would drive me an hour east to attend a community Chinese school. Located in the heart of a growing Chinese American enclave, this school became the focal point of my Sundays. For a seven year old kid, the ritual was borderline tortuous — an hour spent carsick, immediately leading into 3 hours of language classes, followed by school wide presentations or announcements. The one thing I would always look forward to, was after our lunch break, they would pack us all into mini-vans or Toyota sedans and shuttle us to the nearby recreation center, where we would all file out for two hours of exercise and activities. For me, that always meant pickup basketball.

Looking back on those experiences, it must have been such a strange scene for the locals: a herd of hyperactive Chinese kids spilling onto the courts every Sunday at 1pm, shepherded by bespeckled and balding dads yelling jia you!. Here was a space for us to cultivate our love for the game, in a sport that had not a single person who looked like us at the time. And on those Sundays, we took that game and built our own world and rules. We were all short and skinny, so you could play center if you wanted, or point guard, or both. Our fathers were giants, the older brothers to be admired with their brand new Jordans and baggy shorts.

As I moved into middle school and then high school, I began to understand the world had different expectations for what role I got to play. I was cut from my junior high team, the summer basketball camps I begged my mom to attend had nary a kid that was as obviously Asian as me, and I started to quietly accept nicknames like Jackie Chanand Ni Hao from my opponents (and sometimes my teammates). But there was solace in the fact that now, Sunday school had morphed into after school, and I would lug a duffel across four parking lots after the last bell rung so I could lace up my high tops and run full court for hours until far past dinner time. At this new recreation center, I was joined by some familiar faces — Chinese kids I had grown up balling with — except now, the courts were also ruled by Koreans, Indians, Vietnamese, and Filipinos. My high school was 12% Asian, but that rec center might as well have been in Chinatown.

On February 4th, 2012, Jeremy Lin scored a career high of 25 points against the Nets that barely registered on most sport fans’ radars. A week later, he dropped 38 on the Kobe-led Lakers, and Linsanity was officially on. There were more moments that I can never forget — watching his game winning three against Toronto on a buffering live stream on my buddie’s 20 inch monitor, gleefully picking him up for my fantasy team and gloating to my group text of friends, rushing home from class just so I could if there had been another article released about this surreal moment. There’s been enough written about what Jeremy Lin represents to a generation of Asian Americans who grew up as the NBA was absolutely culturally taking off. As a kid, I fantasized about hitting the game winning shot for my high school team, or dunking in traffic in front of an audience of my classmates. When Linsanity happened, it was an obvious projection of those childhood fantasies into the most prestigious arena. What surprised me though, was how easily the Asian Americans around me in college at the time, all revealed and shared those exact same fantasies.

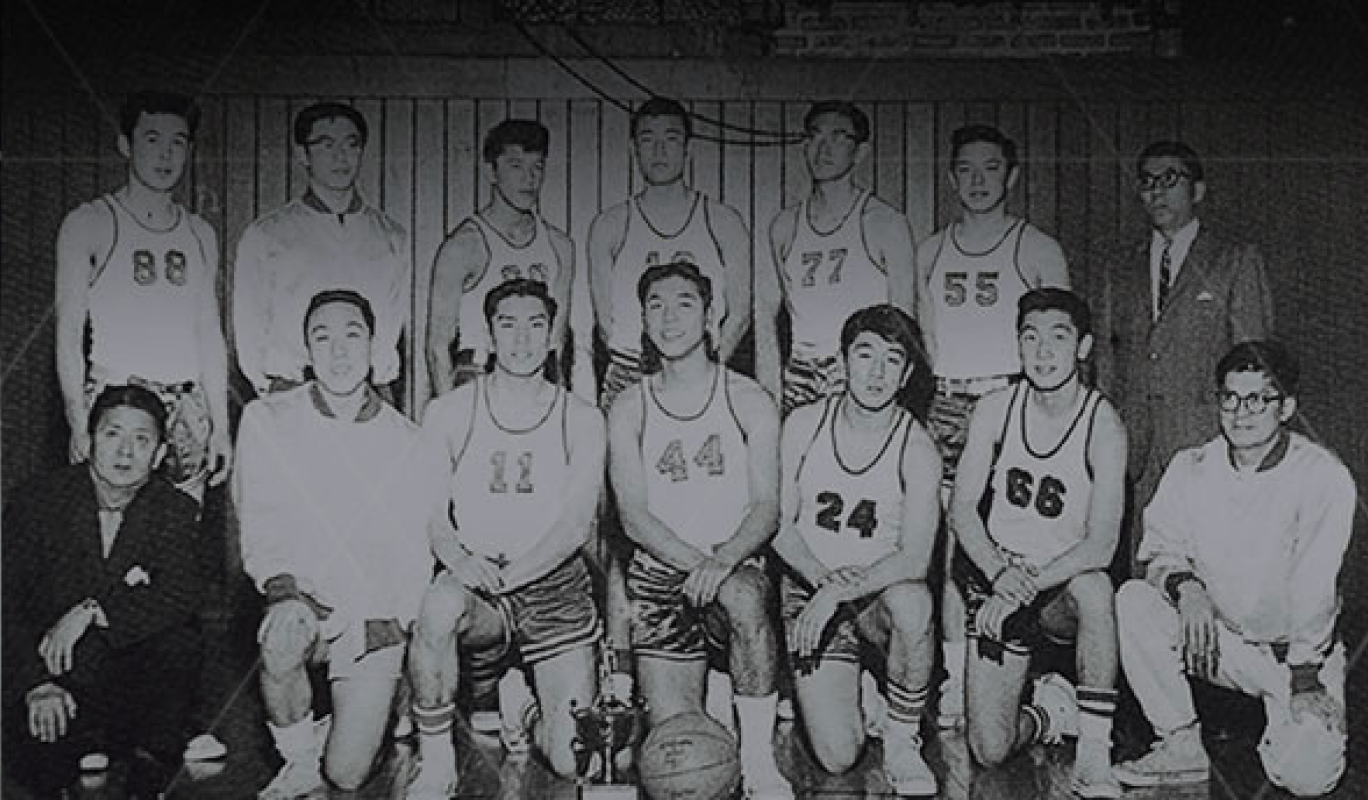

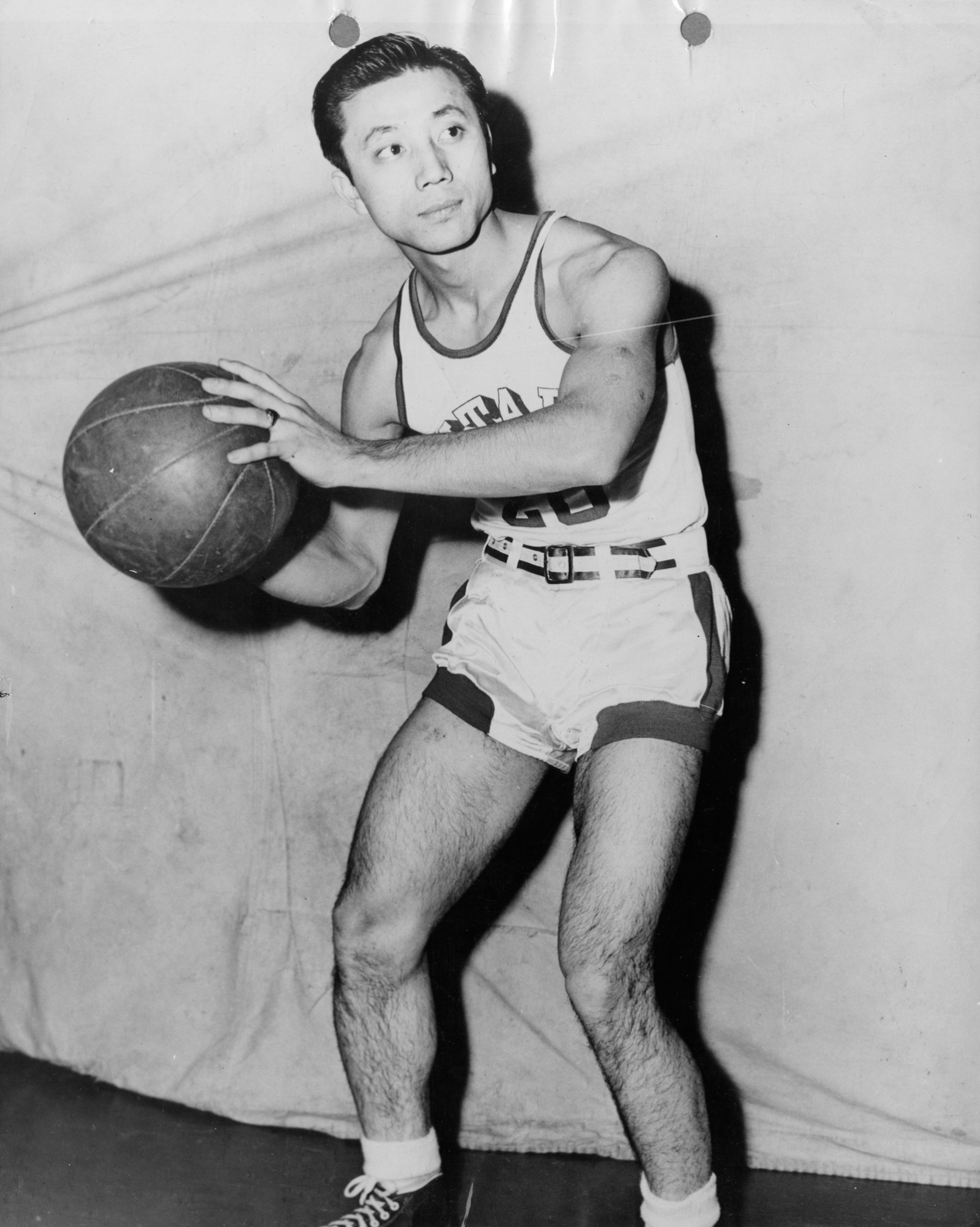

Asians being crazy about basketball didn’t start with Linsanity. It didn’t start with Double Ten, the area Asian American basketball tournament that I played in almost every summer. And it definitely didn’t start with a shushu organizing some layup drills after Chinese school. You could maybe say it started in 1947, when Wataru Misaka became the first Asian American player in the NBA. But really, it probably goes back to 1919, when San Francisco’s Chinatown Boy Scout troop fielded a team to compete with other locals, the first recorded Asian American organized basketball team in the US. By the 1940s, there were traveling basketball troupes called the Hong Wah Kues or the San Francisco Saints that played other teams across the United States — William Woo Wong was actually Lin’s precursor at Madison Square Garden, making history by playing at the famed arena in 1950.

Starting with those Chinatown teams in San Francisco, the Asian American journey blossomed: first Chinatowns in New York, to now when you can spy an Asian balling at almost any outdoor court across Manhattan, Queens, and Brooklyn. Outside SF to the rest of the Bay Area, with basketball crazed Pinoys in Daly City sporting freshly lined up fades and crisp Jordan 1s. The newer gen Taiwanese in the SGV, rocking purple and gold warmups to their local suburban rec centers. Where you walk into a banh mi shop in Houston, and there might be a Vietnamese kid repping an old Stevie Franchise jersey. Why has this sport proliferated to this minority community so extensively, to the point where it’s completely unsurprising that online basketball forums tend to be dominated by Asian American participants, and no one blinks an eye when the university gym is majority Asians playing pickup?

There’s a part of me that likes to imagine that Boy Scout troop leader back in 1919, trying to positively channel his teenagers’ energy with only a ball and a hoop, and inadvertently pioneering a nationwide Asian American sensation. There’s probably a bit of truth that this whole phenomenon was part circumstance, much in the same way the shushus in my Texas suburb were looking for a convenient (and free) way to burn out a bunch of 7 year olds.

For me and my friends, coworkers that I’ve met, strangers that I’ve talked to — basketball was our doorway into American culture and some form of assimilation. It was an arena for us to feel cool and confident, when so many of our experiences and what we were exposed to told us the opposite.

I went back to the Richmond rec this past weekend, and in an uncommon spurt of inspiration, decided to join in a game with a group of high school kids. The court had been freshly buffed, and our shoes squeaked melodiously against the surface. I could see a reflection in the sheen that contained not only my own childhood, but also those of the early 1900s Chinatown Boy Scout troops, Wataru Misaka, and perhaps Jeremy Lin. The boys played with innocent joy and bravado, every move imbued with an ostentatiousness that I had long since purged from my game. To them, basketball was their sport, and there was nothing anybody could tell them otherwise.